Forward Ever! Remembering and Teaching about Emancipation, Freedom, and Pan-Africanism in Canada7/25/2014

“...we shall go forward, upward, and onward toward the great goal of human liberty.” – Marcus Garvey, The Future as I See It, 1922 August 1st, 2014 is a significant date in African history for two reasons. It marks the 180th anniversary of the legislation that abolished the enslavement of Africans throughout British colonies. This year also marks the 100th anniversary of the formation of the Universal Negro Improvement Association by the Honourable Marcus Mosiah Garvey. This occasion is deserving of a longer-than-usual blog post to unearth the relationship between both anniversaries and their relevance to today. Emancipation Day Celebrations After receiving Royal Assent in August 28, 1833 the Slavery Abolition Act took effect on August 1, 1834, ending the brutal practice of African enslavement throughout the British empire. However, it took until August 1, 1838 for former slaves in some Caribbean islands to be fully freed. The passage of this monumental piece of legislation was truly an occasion for celebration – almost 1 million Africans were freed in the Caribbean, South Africa, and a small number here in Canada. Montreal was one of the first sites of Emancipation Day commemorations held on the very day the Act took effect. Since then the recognition of Emancipation Day has become a remarkable display of African-Canadian tradition and spiritual restoration nation-wide. The day was celebrated across Canada in many villages, towns and city centres. Black men and women of diverse backgrounds along with White and Aboriginal supporters commemorated Emancipation Day through participation in street parades, church services, lectures, dinners, dances, and other activities. I detail the history, the features, organization, and evolution of the annual commemoration, and the celebration’s links to Caribana in my two books Talking About Freedom: Celebrating Emancipation Day in Canada and Emancipation Day: Celebrating Freedom in Canada. The passage of the Slavery Abolition Act was just the beginning of the global movement, including here in Canada, for full rights and equality for people of African descent. The struggle for human rights began immediately after emancipation. Emancipation Day was a major celebration, but was also used to mobilize people in the fight to end African slavery in the United States and as a platform to bring awareness to the many social and political barriers faced by African Canadians well into the twentieth century – segregation in housing and public education, access to post-secondary programs, exercising the right to vote, fair employment opportunities, the right to purchase government-owned land, the right to be served in barbershops and restaurants, and the right to be accommodated in hotels. Even in celebrating Emancipation Day Blacks faced discrimination as invited guests and visitors could not stay or eat in some establishments in cities such as St. Catharines, Windsor, and Dresden. Celebrating Emancipation Day continues today in places like Owen Sound, Windsor, Dresden, and in Toronto where for the second year, Itah Sadu and A Different Booklist will host the Freedom Train on the TTC subway on the night of July 31st to symbolically ring in freedom at midnight. The Universal Negro Improvement Association Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey and his wife Amy Ashwood formed the UNIA on August 1, 1914 in Jamaica because of the date’s historical significance. Garvey viewed Emancipation Day as “a sacred and holy day...a day of blessed memory.” The aim of the worldwide organization was to further the human rights agenda through the promotion of racial uplift through Black agency. Garvey and his movement had a strong influence on African Canadians. During the 1920s and the 1930s fifteen UNIA branches opened in Canada. Garvey established strong ties with Canada early on in his Black nationalist movement. African Canadians, especially those who emigrated from the West Indies during this time, were drawn to his philosophy and were eager to support the expansion of the UNIA. The first Canadian branch of the UNIA opened in 1918 in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia. The Toronto branch opened up in 1919 and was visited by Garvey. By the early 1930s there were five branches in the Maritimes, one in Montreal, Quebec, four in Ontario, three in Alberta, and two in British Columbia. All UNIA branches opened halls that served as political meeting places as well as community and social centres. This was an important benefit to members of Black communities because they often experienced segregation and were not welcome in White venues. Garvey spent some time in Canada in the summers of 1936, 1937, and 1938. Due to legal troubles stemming from the operation of the Black Star Line and eventual deportation from the United States, Garvey decided to use Canada as a base for UNIA business during those three years. UNIA regional conferences were held in Toronto in 1936 and 1937. In 1938 the eighth and last International Convention of Negro Peoples of the World was also hosted in Toronto. These gatherings were attended by supporters in Canada and from the United States. Garvey also toured several places in Canada and gave speeches in various places including Toronto. While speaking at a church in Windsor on September 25, 1937 Garvey remarked, “The purpose of the U.N.I.A. is to emancipate and our primary duty is to emancipate your minds because it is the mind that makes the man, that directs him. It is the mind that makes the man, the race; and all that you see material, artistic and otherwise of nature is man's mind working upon Nature.” The words from his Sydney, Nova Scotia speech delivered on October 1, 1937 influenced Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song”: “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind. Mind is your only ruler, sovereign. The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be a slave of the other man who uses his mind, because man is related to man under all circumstances for good or ill.” The Toronto UNIA branch organized the annual Emancipation Day celebrations in St. Catharines, Ontario called the “Big Picnic” from the 1920s to the 1950s. Garvey addressed the huge crowd that gathered to celebrate Emancipation Day at Lakeside Park in 1938. While in Toronto in 1937 Garvey launched the School of African Philosophy to train future UNIA leaders, where he taught summer classes on Black history and. Garvey returned to London, England where he died of stroke on June 10, 1940. Marcus Garvey’s philosophy resonated with many in the African Diaspora. He encouraged Blacks to be proud of their African heritage and inspired many Black nationalist activists to advance the Pan-African unity movement. Garvey called for Africans to emancipate themselves from bondage in many forms – economic, political, and psychological. Garvey’s Legacy His lasting legacy is still evident in the names of the buildings, streets, and places of learning that memorialize his name. In Canada, the Toronto, Montreal, and Glace Bay branches of the UNIA remain active today on a smaller scale. The Marcus Garvey Centre for Leadership and Enterprise was established near the Jane and Finch community of Toronto in 1996 in his honour. In 2007 the Marcus Garvey Centre for Unity opened in North Edmonton, Alberta to serve Jamaican Canadians and other residents of that community. Marcus Garvey Day has been commemorated annually in Toronto on his birthday on August 17th since 1993. Due to the efforts of African-Canadian individuals and community organizations along with other groups, human rights was and is very much part of the national policies of Canada. Basic civil rights and fundamental human rights and freedoms have been enshrined, protected, and enforced by numerous pieces of legislation such as provincial and federal human rights codes and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. More Work to Do For me, recognizing August 1st, 2014 is as much about marking these two milestones as it is about charting a future course because complete freedom and equality has yet to be realized. This is evidenced in the direct historical connections with the present-day social conditions of Black and Aboriginal peoples both once enslaved and colonized, including here in what is now Canada. Both groups have been criminalized and experience racial profiling, over policing and high incarceration rates. They experience discrimination in the labour market that result in high unemployment and under-employment rates regardless of their levels of education. The Canadian education system fails to reflect the faces and experiences of these groups, resulting in high dropout rates. So why should and how can Emancipation Day, Marcus Garvey, and the UNIA be covered in Canadian elementary and secondary classrooms? In interrogating the pursuit of social justice and political activism with learners, these topics present opportunities to critically explore the history of civic engagement and the evolution of the human rights movement in our country. Black students can link themselves to a history of social activism that was taking place across the African Diaspora. Examining the development and evolution of a Black cultural tradition in Canada that spans almost 200 years situates people of African descent firmly in the nation building foundation of the country. These stories and images must be shared with students of all backgrounds to foster a deeper awareness and appreciation of the experiences and contributions of Blacks in Canada and enable critical learners to identify the legacy of racism that affects us today. Students can learn about the importance of united efforts to combat racial inequality to effect legal and social change. Young people can also critically reflect on what human rights and freedom means today, identify who experiences restricted freedoms, and how they can participate in moving Canada towards full human rights for all of its citizens “so that one day, future generations will be able to celebrate true freedom.” Honouring the memory of Emancipation Day and the UNIA involves employing education in furthering the cause of freedom, just as the freedom activists of the past knew this importance. Suggested Resources: Slavery Abolition Act, 1833 article by Natasha Henry Marcus Garvey Speech delivered in Windsor, Ontario on September 25, 1937 The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, volume VII edited by Robert A. Hill, 1990. The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, edited by Amy Jacques-Garvey, 1977. Blacks in Canadian Human Rights and Equity History timeline, poster, and lesson plans "The Universal Negro Improvement Association" video clip in Slavery: A Canadian Story in the Hymn to Freedom series (Available on Learn 360). African Diaspora by Natasha Henry (Forthcoming in 2014)

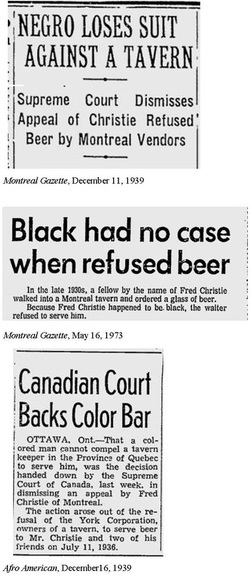

“The root cause of [racial discrimination] is ignorance. People act this way because they don’t know any better and education will bring them out of this. And the law will force the people to educate them because the law will have a penalty attached to it if they break the law and they’ll have to suffer a penalty, so they’ll be prepared by being educated, not to discriminate.” - Rev. Emerson Andrew Talbot (Queen Street Baptist Church, Dresden), Dresden Story, 1954 On July 11 1936, African Canadian Fred Christie was refused service at the York Tavern in the Forum in Montreal after watching a Canadiens hockey game with friends. Christie sued and won in provincial court. Christie was awarded $25 and the tavern was ordered to pay his court costs. However, the tavern owners successfully appealed. Determined, Christie took his case all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. They dismissed his case, arguing that private businesses and discriminate based on race. The high court did not see that denying service to a person because of their race was "contrary to good morals or public order." Fred Christie’s brave stance ushered in another chapter in the freedom movement of African Canadians. Hugh Burnett also entered the battle against racial discrimination during the month of July. In July 1943, Burnett, who just returned from serving in Europe, wrote a letter to federal Justice Minister Louis St. Laurent to complain that he was denied service at a Dresden, Ontario restaurant while donning his military uniform. St. Laurent replied that racial discrimination was not against the law in Canada. Burnett began his participation in a growing movement to push for this legislative change. Members of the National Unity Association (which included Hugh Burnett), Bromley Armstrong, and many Black Canadians along with other human rights activists such as Ruth Lor Malloy, used Dresden as the "battleground" in the fight for human rights legislation. Success finally came with the enactment of the Fair Accommodation Practices Act passed on April 6th, 1954. The 60th anniversary of the passage of the Fair Accommodation Practices Act passed three months ago without acknowledgement by the government at any level, an article in the press, or coverage in the news. Armstrong has justly received personal accolades including the Order of Canada and the Order of Ontario. Hugh Burnett and his organization, the National Unity Association, received a plaque four years ago, but that is the only public memorial for people who played a pivotal role in turning the tide in the struggle against racial discrimination. The Kielburger brothers pointed out the glaring absence of their names on a list of influential Canadians in a recently published article, Why Are There Mostly White Males on the Canadian Heroes List? The existence of the Fair Accommodation Practices Act, Human Rights Codes, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the immigration points system, are due in no small part to the efforts of Black activists who pressed and agitated for equality and human rights. How can citizens call for a social justice agenda when we continue to deny the reality of the fight against racial injustice in our own society? We could learn something from our neighbours to the south who bring their history, however tainted, to the fore, acknowledge their past, and honour the work of civil rights activists. In the United States, to mark the Freedom Summer and the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Acts, there were documentaries and discussions on public and private television networks, educational organizations made it a point to increase public awareness through youth forum, workshops, and learning resources. Archives digitized and made public images and documents. President Obama saw fit to address this civil rights milestone at least one speech. It is important for students in Canadian classrooms to learn about the historic inequalities experienced by African Canadians and their legacies that remain with us today. The stories of the men, women, and groups involved in the human rights movement and who served as agents of change should be taught. The present-day implications and unfinished business of the Canadian journey toward equality need to be part of the exploration of civic engagement and social justice. As part of my commitment to bringing this information into the classroom, I have been working with Turner Consulting Group to develop a curriculum resource, “Black in Canadian Human Rights and Equity History.” These lesson plans and other resources for teachers will be launched in September 2014. It is our hope that elementary and secondary school teachers will be encouraged to use these learning materials to teach students about Canada’s human rights movement and motivate young people to continue the fight against racism in its many manifestations. Hopefully when then next set of anniversaries roll around, these front line activists will get the respect and public memorialization they rightly deserve.  Fort Mississauga Fort Mississauga “I further Certify that the Said Richard Pierpoint, better known by the name of Captain Dick, was the first colored [man] who proposed to raise a Corps of Men of Color on the Niagara Frontier, in the last American War; and that he served in the said corps during the War, and that he is a faithful and deserving old Negro.” – Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel Coffin, Adjutant General’s office, York, July 21, 1821 In 2014, there has been a lot of hoopla about the many war commemorations that will be recognized this year – the 100th anniversary of WW1 and the 75th anniversary of WW2. The 2-year long Bicentennial commemorations of the War of 1812, which began in 2012, also continue. War of 1812 enthusiasts and historians are set to mark the 200th anniversary of Battle of Lundy’s Lane on July 25th and as it approaches, I am called to reflect on the fact that there is very little public knowledge about the involvement of African Canadians in the War of 1812. Its omission from teacher resources, and consequently from our classrooms, is a contributing factor. Three months ago, I picked up a new book in a school library that was released in 2013. There was not one mention or image in reference to Black men fighting in the War of 1812 in defense of the British colony now called Canada. In a 2012 article, a parent shared that a teacher told his child that the information in his presentation was incorrect, because Blacks did not fight in the War of 1812. When a three-episode documentary commemorating the 200th anniversary of this North American conflict aired on public television, I watched disappointed in the glaring omission after its three-week run. The Battle of Lundy’s Lane on July 25th 1814, was one of the bloodiest and most important engagements fought and upwards of 80 Black men were there. Richard Pierpoint and his all-Black militia unit, the Coloured Corps, the Black soldiers of New Brunswick’s 104th Regiment, and the Black men enlisted in other militias or regiments, helped to make the Battle of Lundy’s Lane a British victory. The Bicentennial of the War of 1812 provides a timely opportunity to learn about the men of African descent in Upper Canada, Lower Canada, and the Maritimes who risked their lives defending British interests in North America (many for the second time). They were willing to die for freedom in their roles and contributions as soldiers, sailors, and construction workers. Furthermore, until now, the war’s impact on their wives and children was not even considered. Their wives and children were subject to extreme hardships, loss of property, displacement, and food insecurity, like others in the civilian population. And so for me, this is one of the “battlefronts” in my effort to disseminate this historical information to young people in Ontario classrooms as to date, there is not one specific learning expectation on the African Canadian experience in the curriculum, despite a presence that dates back at least to 1604. I am grateful to have been part of two projects that ensure that their stories are never forgotten. As the Education Director with the Harriet Tubman Institute at York University, I was part of an incredible team dedicated to contributing brand new research on Black participation in the War of 1812 through the creation Augmented Reality digital stories. I developed the learning materials for this research to make its way into classrooms. We Stand on Guard for Thee: Teaching and Learning the African Canadian Experience in the War of 1812 (*MARKER REQUIRED) As a consultant for Historica, I provided historical advice for the Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute and developed the supporting learning resources. This initiative provides a visual representation that is sorely lacking in the Canadian perspective of the war. Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute and Teaching Resources Heritage Minute Learning Tool Supplement Learning Tool Resources These resources contextualize the experiences of African Canadians during the war, which is essential to critical historical thinking. Questions related to Black participation in the War of 1812 that can help to establish context and guide inquiry-based learning include: - Who were the men that fought? - What challenges did they face? (e.g. segregated service, injury) - Why did Black men, formerly enslaved and free, fight? - How did they contribute to the war? - What were their lives like after the war? - Where are their descendants today? We Stand on Guard for Thee and the Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute share a range of primary documents that can be used in the history classroom to explore these questions and embed the content in the inquiry process. Both projects also recognize and celebrate the fortitude of African Canadians during the early 1800s. Practices of remembrance such as the bicentenary of the War of 1812 that include the African Canadian narrative can help to reduce the alienation experienced by students of African descent. For students of African origin, seeing themselves in the curriculum can assist in the exploration and formation of a group identity while nurturing personal investigations of self-definition. They can rightly and proudly locate Blacks on the Canadian landscape, linking the past to the present. Additionally, it can work to address the effects of systemic exclusion by increasing student engagement through inquiry. The legacy of their military service and settlement needs to be taught in schools to increase public knowledge, to broaden the Canadian historical narrative, and to diversify the image of who early Canadians were. I honour their memory by writing them into Canadian history to educate generations to come. Additional Resources: A Stolen Life: Searching for Richard Pierpoint by Peter Meyler and David Meyler, Natural Heritage Books, 1999. To Stand and Fight Together: Richard Pierpoint and the Coloured Corps of Upper Canada by Steve Pitt, Dundurn, 2008. Fountain Thurman: Black Freedom Fighter Referenced: Education Director Natasha Henry on Black Loyalists in the War of 1812 Battle of Lundy’s Lane |

AuthorNatasha Henry Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||