|

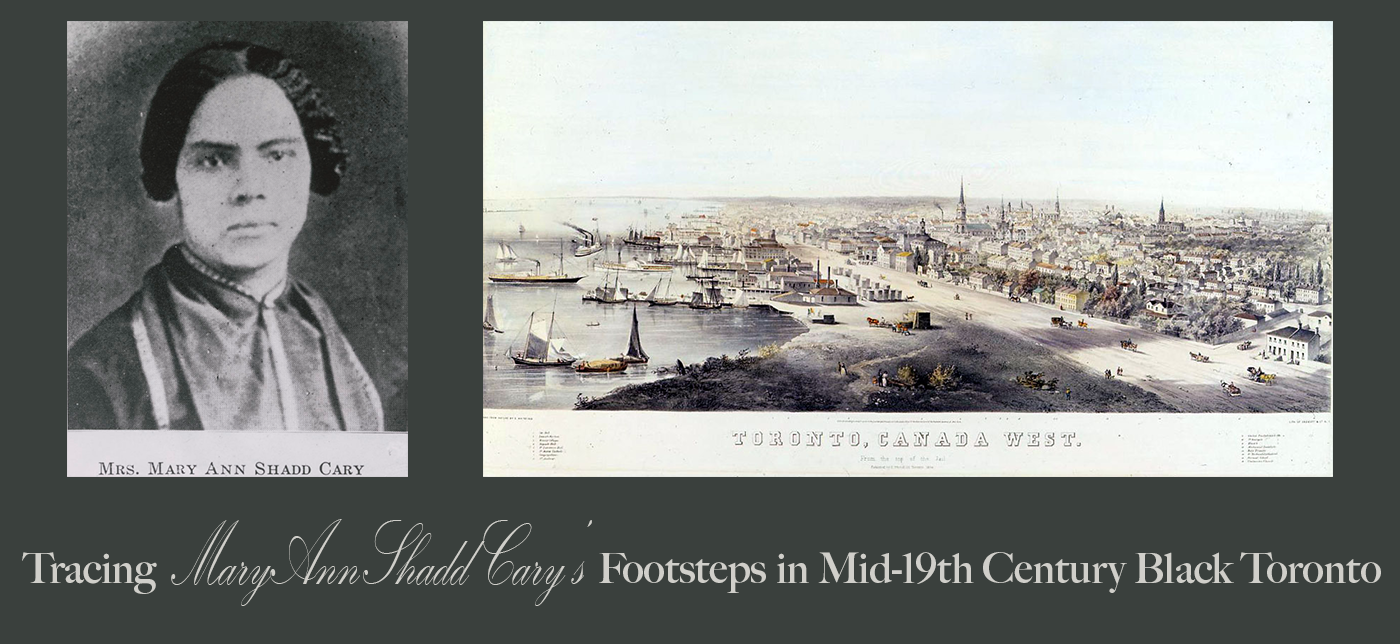

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s birthday (October 9, 1823–June 5, 1893). Shadd Cary was an antislavery activist, educator, and a trailblazing newspaper editor, journalist, and publisher of the newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. She was born in Delaware and grew up in Philadelphia. Shadd Cary moved to Canada West (Ontario) in 1851 and spent eleven years in the province (1851 - 1863). She had a huge impact on the lives of Black people at the time and left an unforgettable legacy. Here are a variety of resources to learn more about Mary Ann Shadd Cary and to teach about her life and significance in classrooms. Register here [SOLD OUT] Publications by Mary Ann Shadd Cary Articles and other writings by Mary Ann Shadd Cary, The Black Abolitionist Archive in The Archive Research Center at The University of Detroit Mercy “Images from Archives of Ontario - F 1409 Mary Ann Shadd Cary Fonds,” Wikimedia Commons. Library and Archives Canada online documents from the Mary Ann Shadd Cary Collection

In Canada, history is only ever taught one way.

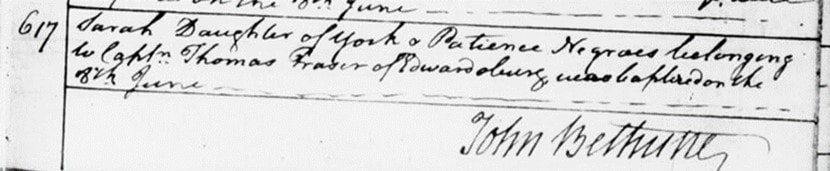

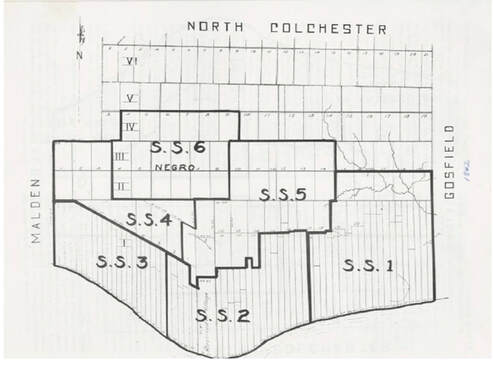

To prove this, we blacked out all of the non-Black history from a 255-page history textbook. Only 13 pages remained. To demand change, use #blackedouthistory. My dissertation, One Too Many: The Enslavement of Africans in Early Ontario, 1760 – 1834, focuses on the enslavement of African men, women, and children in Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) between 1760 and 1834. I am examining the scale and scope of the enslavement of African people in early Ontario, contextualizing this historical reality within the global phenomenon of the Transatlantic slave trade, French and British colonization of what is now Canada and the “New World”, and the American Revolution, which resulted the Loyalist exile to British North American and the forced relocation of the Africans they enslaved. My hybrid dissertation includes the creation of an open-access database that will provide a comprehensive enumeration of enslaved Africans held in bondage, the first major scholarly effort to do so. My employment of Black digital humanities involves the the development of biographical narratives of a number of subjects of my research, to ensure that their humanity and contributions are honoured and their memory, often denied, is acknowledged. I intend for my study to be a valuable research and educational tool. Slavery in Canada was included in the learning expectations of the Ontario Social Studies, History, and Geography curriculum for the first time in 2013. However, it is only an optional topic for grades 3 to 7. To encourage the use of my research in classrooms, I will draw on my curriculum development expertise to create instructional resources that will support the teaching and learing of slavery in Canada at the elementary and secondary levels. My goal is for my research to contribute substantially to Canadian slavery historical scholarship, public knowledge, and to the teaching of slavery in Canada.

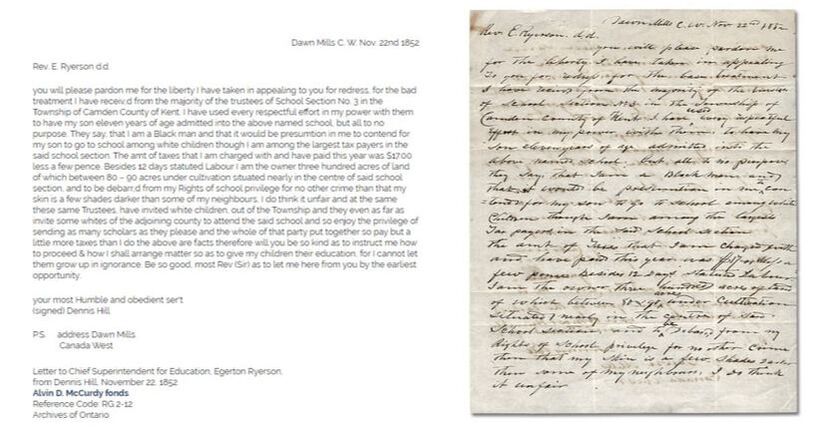

Stay tuned for more information and updates. York Celebrates Recipients of Prestigous Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, July 2018 Graduate Student Profile in History Matters Winter, Spring 2019 Profile in York University Magazine, Winter 2020 “When Black history and Black contributions are denied in the curriculum and by those who teach it, Black people are themselves denied.” – Teaching for Black Lives, Rethinking Schools This week, February 3 – 7, 2020, is the #BlackLivesMatterAtSchool Week of Action. The timing of this week of action coupled with the current state of affairs in Ontario and across Canada pertaining to Black children and Black families in the public education system, it is an opportune time to learn about and reflect on the long history of anti-Black racism public education in Ontario and across Canada, which continues to remain a reality. I provide a brief description of that history in my research brief discussion paper, Anti-Black Racism in Ontario Schools: A Historical Perspective. This growing activism is a 21st century iteration of the ongoing movement for racial justice for Black children in state educational institutions beginning from post-emancipation, through to the Civil Rights Movement, through to the Black Power Movement, through to today. We must also be reminded of the long history of advocacy and organizing by Black parents, Black communities, and Black educators in pursuit of the eradication of the education debt owed to Black Canadians in Ontario. Dr. Ladson-Billings argues that we need to look at the "education debt that has accumulated over time. This debt comprises historical, economic, sociopolitical, and moral components." Understanding the legacies of educational inequities experienced by Black children elucidates today's outcomes and should be used to guide the actions needed to address persistent anti-Black racism. What is the education debt to Black children given the history? This week of action encapsulates everything that has been going on in Ontario over the past few decades and functions as a reminder of the universality of anti-Black racism in educational systems. These five days are a call to action to interrupt and dismantle educational policies and practices that harm Black youth. The four central demands are: End Zero Tolerance This speaks to the issue of the discipline of Black students and the ways they are criminalized in school spaces. One aspect of this issue that Black communities have raised is SRO programs in schools and how police officers in schools are sometimes used to discipline Black students. An extension of this issue is the role of the educational system in feeding the school-to-prison pipeline. Black communities are seeking solutions such as culturally relevant counselling support and the use of restorative justice to address the racial disparities in discipline.

Fund Counselors This demand asks educational systems to pay attention to and invest in services that support the mental health and well being of Black children and to address/remove the conditions that negatively impact the healthy development of Black students, such as dealing with the use of the n-word and other racial slurs.

More Black Teachers The first Black teacher and Black principal in Toronto was Wilson Brooks in 1952 although Black students have attended public schools in that city since its inception in the 1800s. This demand is self explanatory and raises the issue that communities have expressed that teachers should better reflect the changing demographics. Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of Black teachers to all students, particularly Black teachers with an antiracist pedagogy. It also raises the issues of the working conditions of Black teachers and administrators, as well as the promotion and retention of Black educators.

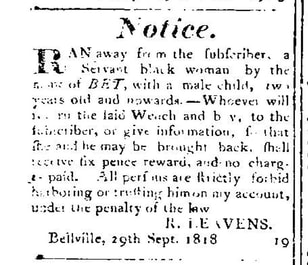

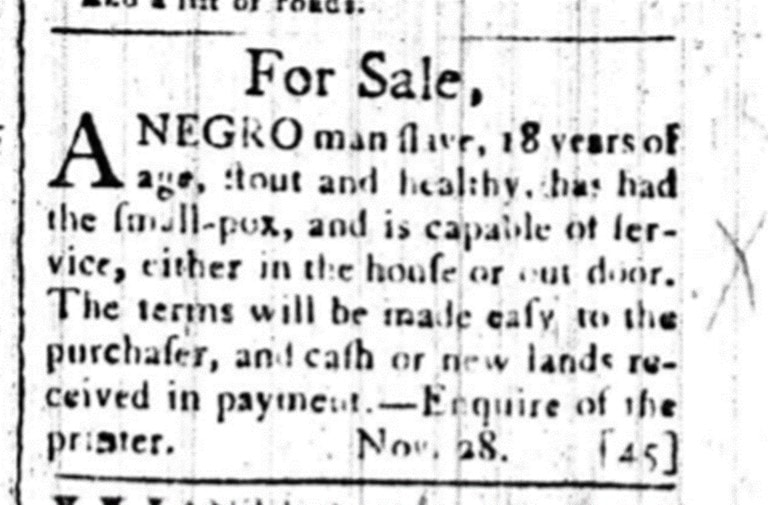

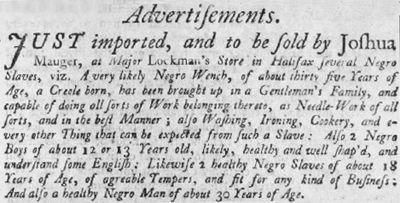

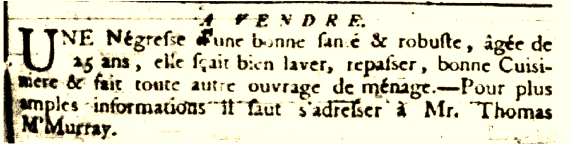

Mandate Black History & Ethnic Studies This demand seeks redress for the systematic exclusion of African and Black peoples from the official curriculum and a corrective approach to the problematic representation of Black peoples. A quote from the book Teaching for Black Lives succinctly summarizes this: “When Black history and Black contributions are denied in the curriculum and by those who teach it, Black people are themselves denied.” This demand calls for Black and African histories to be constitutive of, not merely add-ons to the provincial curriculum. There is not one specific learning expectation about Black Canadian history that all students in Ontario have to learn, despite a 400-year presence on these colonized lands. I have researched and written about how Black history is taken up in the Ontario SSHG and CWS curriculas in my masters research project, Lend me Your Ear: the Voice of Early African Canadian Communities in Ontario through Petitions and more recently in my chapter contribution, “Where are the Black People? Teaching Black History in Ontario, Canada”, in the book Perspectives of Black Histories in Schools. My website came about as a response to the exclusion and absence of Black people in the curriculum. Black History Month was born out of the activism to address the particular forms of exclusion, erasure, and representation of Black history. In the 1920s when Dr. Carter G. Woodson established Negro History Week which evolved into the month-long observance that we recognize today. There are many studies that discuss the demands from Black students and parents for Black history in the curriculum and describes how this exclusion is a pernicious form of neglect, trauma, and infringement of human rights such as Towards Race Equity in Education by Dr. Carl James, The Roots of Youth Violence Report by Roy McMurtry and Dr. Alvin Curling, the Stephen Lewis Report on Race Relations in Ontario, and this recently published article, Ending Curriculum Violence. The Ontario Human Rights Commission states that: “The Code guarantees each person the right to equal treatment in the service of education, without discrimination based on the grounds of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability. This includes equal access to and benefit from Ontario’s education system…” One of the recent recommendations of the OHRC to education systems to uphold the human rights of children in their charge is to “enhance the curriculum to reflect diversity and include content on human rights.” Further, many studies discuss the benefits of the integration of Black historical narratives for Black students and by extension, all students. Across Ontario & Canada There is the misperception of anti-Black racism in education as being only interpersonal and localized meanwhile the broader, systemic, and interconnected operation of anti-Black racism in education is ignored. Looking back only four years in Ontario, there are several instances where concerns of anti-Black racism has been raised: Durham DSB, York Region DSB, Waterloo DSB, Ottawa DSB, the Ministry of Education review of Peel DSB, Halton DSB, and as I started writing this blog post yesterday, Black and Muslim students in the Hamilton-Wentworth DSB held a press conference on racism and Islamophobia in schools, outling some key demands. We can extend westward to British Columbia in the Vancouver School Board. What these examples illustrate is the need for province-wide government and community strategies as well as a national coalition. The ongoing labour action going on across the province has had an impact on efforts to address the needs and concerns of Black students. Many educators have expressed that cuts to education disproportionately affects marginalized and underserved students and that’s part of why they are fighting. This week should serve as reminder that anti-Back racism doesn’t take a break, and as such serving Black children in a more equitable and just manner is not mutually exclusive from meeting the learning needs of Black students during the instructional day nor is it an optional side project. The lens to operate from is to understand and address the myriad of interconnected ways that the system inflicts oppression on Black students, not view Black students as impoverished, lacking, and in need of fixing. This Week of Action encourages all stakeholders to engage in deep learning and unlearning and to organize to take action that will create systemic change to improve the educational experiences and outcomes of Black students.Teachers and students look at the various ways that the movement for racial equity in education has taken shape. One example shared is the New York City school boycott that took place on Feb. 3, 1964. Black communities in Ontario have also been persistent and vigilant in their advocacy and their activism has taken many different forms since the 1800s, from writing letters and petitions to then superintendent of education (what we would now call Minister of Education) Egerton Ryerson, marching in protest against segregated schools in Chatham on Emancipation Day, filing lawsuits, keeping their children home to boycott segregated schools, and today attending school board meetings, running for the position of school trustee, demanding responsive solutions such as the Africentric Alternative School, organizing freedom schools, and speaking their truths that have been documented on video and in reports. The goal has always been and continues to be to achieve a future that is full of possibilities and free from racial inequities and harm and the intentional creation of learning environments where Black children can thrive. The #BlackLivesMatterAtSchool Week of Action builds on the tradition of fighting for equity, justice, and liberation. Carry on. “Speak to me. Tell me everything. Do not forget.” - Biton, Chief of Sama, Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill I am thrilled about the release of the Book of Negroes six-part mini-series. I waited in eager anticipation for this month when it would finally be aired. Why you ask? As an historian and curriculum consultant who specializes in African Canadian history, I am very aware that there are not enough opportunities to see on-screen depictions of the experiences of Black colonists in Canada. This is a much-welcomed rare occasion. I was thoroughly captivated by the novel. Three Christmases ago, I stayed up late into the wee hours of the morning to read the book, the illustrated edition signed by Lawrence Hill, over the course of four days. It was such riveting storytelling and I could not put that book down. I was further enthused when I was asked a couple of months ago to lend my consulting expertise to revise Historica’s Black History Education Guide 2015, a teaching resource for the Book of Negroes novel, to include the widely anticipated mini-series. Another reason for my deep interest in seeing the novel come to the screen is that for a segment of the story, this moving narrative centres the Black female Loyalist voice within the realm of Canadian history, a space where the Black Canadian experience continues to be excluded or marginalized. Aminata’s story and the experiences of Black United Empire Loyalists can be taught through grades 6 to 12 using a wide range of available online and book resources. NEW! The CBC Teacher Resource Guide for the Book of Negroes miniseries is now available! I was thrilled to develop the elementary level portion of the guide. Videos of the Book of Negroes miniseries are available on the CBC website http://www.cbc.ca/bookofnegroes/. Preview all videos before showing in class. For middle school grades, select appropriate segments. The last stop of enslaved Africans before their forced removal from the continent was one of the coastal European slave forts, where they were held in pens. A Virtual Tour of Goree Island provides some insight into the final moments before departure to the Middle Passage. Freedom Child of the Sea by Richardo Keens-Douglas is a picture book that touches on what could have happened to Sanu (the pregnant woman on the slave ship) before Aminata offers to “catch” her baby. This picture book is about spirits of a pregnant enslaved woman and her unborn child, who were thrown overboard a slave ship rescuing a drowning boy. At the time when the Black Loyalists arrived in Canada, they would have encountered enslaved Blacks. There was an active trade in African bodies in Canada. Blacks were bought and sold at auctions, through newspaper ads, and were bequeathed in wills. Approximately the same amount of enslaved Blacks as there were free Black Loyalists were brought in to Canada by white Loyalists entering Canada. Documents related to the enslavement of Africans in Canada are very useful for providing deeper context into Black life in Canada after the American Revolution. Check under “Primary/ Secondary Source Documents” from the Resources chiclet on my website. The actual Books of Negroes, the historical 150-page military ledger, is accessible online. The Nova Scotia Archives digitized the Book of Negroes artefact and made it searchable: http://novascotia.ca/archives/virtual/africanns/BN.asp. This can be used in conjunction with the transcription of the Book of Negroes to allow for an easier read for students: http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/index.htm (see ‘Documents’) Lord Dunmore's Proclamation (1775), which offered freedom to enslaved Blacks who supported the British cause, is available online in original form and transcribed. CBC has created an app called The Book of Negroes Historical Guide. Black Loyalists also settled in New Brunswick. Here are documents and lesson plans for examining the live of Black Loyalists in New Brunswick. Loyalist historian and researcher Stephen has written many copyrighted articles on Black Loyalists. Here is an index of his articles that were published in Loyalist Trails. They are very useful reference materials that provide a bit more insight into the lives of some of the men and women recorded in the Book of Negroes.

Many Black Loyalists remained in the United States. The Book of Negroes, Africans in America Part 2 and Black Loyalists, Africans in America Part 2 by PBS are great resources.

Black Loyalists also entered Canada through the Niagara region, including Richard Pierpoint and several other Black Loyalists. The Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute and the Learning Tool and the Supplemental Activities, which I helped to develop, can be used to teach the perspective of these early settlers. We Stand on Guard for Thee: Teaching and Learning the African Canadian Experience in the War of 1812 uses augmented reality, or digital 3D storytelling to bring a select number of Black Loyalist narratives to life. I developed the lesson plans to support these stories. These are good resources to explore Black Loyalists in southwestern Ontario. My July 2014 Blog "We Would Die for Freedom: Integrating the African Canadian Narrative in the Teaching of the War of 1812," discusses additional resources for teaching about Black Loyalists. Documents Related to Black Loyalists in Canada Here, Black Loyalists, 1783-1792, the Nova Scotia Archives has a range of related primary documents available including passports, petitions, manumission papers, runaway ads, and muster rolls. Books The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783-1870 by James W. St. G. Walker is the book that influenced Lawrence Hill’s interest on this topic. Black Loyalists: Southern Settlers of Nova Scotia's First Free Black Communities by Ruth Holmes Whitehead. Birchtown and the Black Loyalists by author Wanda Taylor. The Canadian publisher of the Book of Negroes developed a teacher’s guide for studying the novel in grade 11 and 12 classrooms. http://lawrencehill.com/BON-Teachers-Guide.pdf The range of lessons on Black Loyalists that can be taught in classrooms must also include lessons that teach students to be critical of how African Canadians have been forcefully removed/ denied space on the Canadian landscape, marginalized or excluded from the Canadian narrative. African Canadians have been physically removed as in the instances of the Shelbourne Riots, the immigration ban in 1911, and the demolition of Africville (many residents of Africville were descendants of Black Loyalists listed in the Book of Negroes). Uncomfortable but necessary conversations need to be had about the persistence of historically racist perceptions as well as the legacy and implications of historical exclusion today. There is also an ethical judgment dimension of the mistreatment of African Canadians that is raised – 206 years of enslavement and a history of racial discrimination and segregation that is not readily acknowledged or widely taught. Making connections to the recently launched UN Decade for People of African Descent (January 2015 – December 2024) can get students to explore how they can contribute to addressing issues of racism and human rights in Canada. In the novel, Chief Biton’s words, “Speak to me. Tell me everything. Do not forget," resonated with me. His words were adapted for the TV screen in episode one in the powerful scene on the slave ship when the men held in shackles called out their names, beckoning the young Aminata to repeat their African names and where they were stolen from. The mini-series offers the space and opportunity to speak about Black Loyalists in Canada, to speak to the harsh realities of enslavement and anti-Black racism in Canada. By engaging this topic in the classroom, students are encouraged to remember - remember the lives, the hardships, the perseverance, and the contributions of Black Loyalist men and women; and remember their names. At almost every workshop I facilitate I am asked by teachers about the availability of resources in the French language to teach about the African Canadian experience. In this post, I have compiled a list to share: NEW! Kayak Magazine Trousse éducative — l’histoire des Noirs NEW! Breaking the Colour Barrier: the Chatham Coloured All-Stars , curriculum francais Black Loyalists in New Brunswick African Nova Scotians: in the Age of Slavery and Abolition We Stand on Guard for Thee: Teaching and Learning the African Canadian Experience in the War of 1812. I worked on this project on Blacks in the War of 1812. Some of these narratives and lesson plans are in French. I developed the learning tools for the Historica Heritage Minute on Richard Pierpoint. Here are the learning resources: Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute Learning Tool Richard Pierpoint Heritage Minute Supplementary Learning Tool The History of Blacks in Canada timeline, also created by Historica, is available in French.

The Archives of Ontario has some online exhibits and lesson plans. Just click on "Francais" at the top right corner of the exhibit page: http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/education/lesson_plans_themes.aspx Please note that the AO lesson plans that support the online exhibits are only accessible from this page under the grades. They have very recently revised the Black history lesson plans, so it appears they are not translated into french yet. Email them to confirm. http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/education/lesson_plans.aspx This website has a mystery lesson plan on Marie Joseph Angelique called Torture and the Truth: Angelique and the Burning of Montreal. While the topic is appropriate for grade 6, as it connects with the revised SSHG curriculum expectations, the lesson plans may have to be modified. Portail du Mois de l’histoire des Noirs - Citoyenneté et Immigration Canada Les Canadiens de race noire en uniforme – Une fière tradition: Anciens combattants Canada Histoire des Noirs au Canada - Historica Radio-Canada célèbre le Mois de l’histoire des Noirs (2013) Mois de l'histoire des Noirs - Immigration Québec Mois de l'Histoire des Noirs - Carrefour Éducation (Québec) Histoire des noirs à Montréal - Mois de l'histoire des Noirs L'ONF célébre le Mois de l'histoire des Noirs (films) I will continue to add to this list. Language adds another barrier to the teaching and learning of the experiences and contributions of African Canadians. Because not all projects that focus on African Canadian history are translated into French, largely due to funding issues, this challenge creates an inequity in accessing Black history. Bien! “The war of complexional distinction is upon us, it is more ravaging to us as a people than that of Mars. But men, as long as this flag shall wave over you, you may rest assured that no man, or set of men, or nations, can successfully grind you down under the iron heel of oppression.” – Committee of Coloured Women (wives of the men of the all-Black Victoria Pioneer Rifles), Vancouver, British Columbia, 1864.

2014 is a particularly significant year for marking Remembrance Day. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the First World War and the 75th anniversary of the Second World War. This blog post to encourage teachers to be intentional in including the stories and experiences of African Canadian men and women in both conflicts as they begin to plan in-class activities and school assemblies. Black men have a long history of fighting in defence of the British colony of British North America (now Canada) and later, the Dominion of Canada, even in the absence of full citizenship rights and discrimination throughout society. At the turn of the 20th century, African Canadians faced discrimination in housing, employment, and education. In 1911, the government of Canada placed a 1-year ban on the immigration of African Americans into the Prairie Provinces. Despite facing racism in society and by the government, hundreds of Black men sought to volunteer their service to defend the colony and country. Sadly however, discrimination extended to military service. When men wishing to enlist attended recruiting centres, they were turned away, a common unwritten practice. Hamilton’s first Black postal carrier, George Morton Jr., wrote a letter to Sir Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence in September of 1915 asking “to be informed if your Department has any absolute rule, regulations, or restrictions which prohibits, disallows or discriminates against the enlistment and enrolment of colored men of good character and physical fitness as soldiers” because “a number of colored men in this city (Hamilton), who have offered enlistment and service, have been turned down and refused, solely on the ground of color or complexioned distinction…” (Letter available under Resources). To meet recruiting demands while addressing the protests of the African Canadian community, the Canadian Militia Department established the Construction Battalion #2, a segregated military unit in which Black men could serve. Raised in Nova Scotia, more than 300 Black men from across Canada enlisted in the Construction Battalion #2, risking their lives to fight and work for a common cause, but separated by race. In the Second World War, Black men once again answered the call of the Canadian military, this time serving in integrated units. Hundreds of African Canadian men deployed to Europe. Some fought on the front lines while others performed equally essential duties in labor units building trenches, roads, and bridges. Hundreds of African Canadian men including Stanley Grizzle and Owen Rowe served as soldiers. The Honourable Lincoln Alexander, Leonard Braithwaite, and Alvin Duncan of Oakville were some of the Black men who served in the Royal Canadian Air Force. African Canadian soldiers hoped that their military service, along with the war efforts of the Black community back home, would translate into furthering human rights for African Canadians. Many were blatantly reminded that nothing had changed. In 1943, Hugh Burnett, was refused a cup of coffee at a Windsor restaurant while wearing his military uniform. Another group of Canadians of colour whose military service should be taught are Sikh Canadians. Sikh men served in the Canadian military in both world wars. Buckam Singh, who immigrated to Canada from Punjab, India as a young boy, served in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces and received a Victory Medal. Nine other Sikh Canadians fought in WWI at a time when Sikhs were barred allowed from immigrating to Canada (see 1914 Kamagata Maru incident). Only Sikh Canadians who served in the Second World War were granted voting rights in 1947. Sources for teaching about the role of Sikh Canadians include:

The military contributions of Aboriginals should also be recognized in our schools. Nearly 10, 000 Aboriginal men and women enlisted and served in the first and second world wars. They served as soldiers, sailors, and nurses. Similar to African Canadians and Sikh Canadian, Aboriginal people faced service restrictions because of their race. Positions of commissioned officers were off limits to non-Whites. Aboriginal peoples volunteered to fight overseas at a time when their communities remained under the grip of the oppressive policy of forced assimilation, with Aboriginal children were being taken from their families and placed in residential schools. The cultures and languages Aboriginal peoples were under perpetual assault and Aboriginal communities were stepping up their fight for the federal government. Their service in the Canadian military is another example of marginalized Canadians battling for equality and human rights on many fronts. Suggested resources:

In spite of and because of the social injustices they experienced, the willingness and resolve of African Canadians, Sikh Canadians, Aboriginals and other groups to serve in the military should be woven firmly into the national Remembrance Day narrative. Infusing these rich stories and varied perspectives challenge the racialized distinction and exclusion still prevalent in national memorials. Incorporating the experiences of these groups in our military helps students to develop a deeper, critical understanding of the racialization of military service and representation in commemorations, what happened in the past and how many of these barriers have been broken down. That means teaching about Black men being turned away from recruiting stations when they presented themselves to enlist and being rejected as volunteers; how their service was restricted because of their race, and how for some, the service of Black men was and has been deemed less valuable even though they fought and died alongside soldiers of European descent; what their lives were like after returning from Europe and how very little changed on the racial discrimination front; that Black mothers such as Edith Holloway, publically mourned their sons who died in combat. Schools play an integral role in shaping public memory. Memory has a strong impact on how an individual sees and locates themselves and others in public spaces and reflected in the national heritage. Practices of remembrance such as Remembrance Day that includes the narratives of people of African descent help to reduce the displacement experienced, especially by Black students. The integration of African Canadian military experiences into the curriculum also teaches students that Canada was built and defended by Canadians of all backgrounds. Additionally, such an inclusion demonstrates that the contributions of African Canadian to the war efforts, who fought on two battlefields – the war theatre in Europe and the anti-Black racism in Canadian society – have benefitted many people. There are direct Social Studies and History connections in grade 2, grade 6, and grade 8. There are also Canadian and World Studies links in grade 10 and grade 12 history, as well as to the new Social Sciences and Humanities courses on Equity Studies. Of course, there are also cross-curricular links to Language, the arts, and other subjects. A wide array of resources, like George Morton’s letter to the federal government, are available to teach about the experiences and narratives of Black Canadians who served in both world wars. Some resources include:

These resources can assist teachers in utilizing varied primary and secondary sources to present a cohesive, comprehensive and historically accurate picture of the war eras and to teach students to analyze the historical impact of war on the Canadian homefront as it relates to Black Canadians. Be inclusive of the African Canadian perspective in Remembrance Day commemorations and acknowledge African Canadians’ struggle for equality in military service and in Canadian society. Black men have an extensive history of fighting in defence of Canada as a British colony and a country going back to the 17th century and Black women have always supported the war effort at home and abroad. It is only right that we never forget that. (Images courtesy of Black Canadian Veterans of War)  Freedom is never granted; it is won. Justice is never given; it is exacted. Freedom and justice must be struggled for by the oppressed of all lands and races, and the struggle must be continuous, for freedom is never a final fact, but a continuing evolving process to higher and higher levels of human, social, economic, political and religious relationships. – Asa Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Labour Day is an opportune time to reflect on the history of Black workers in Canada and as a signal of the new school year, the occasion is a good prompt to think about ways to teach about the history and experiences of African Canadian workers, and the situations facing present and future workers of African descent. People of African descent have laboured in Canada for 400 years. The earliest African workers in Canada were primarily enslaved, forced to work in various capacities without compensation. Because they were considered by law to be chattel property and not human beings, they had no rights. The institution of slavery existed in Canada for a little over 200 years under which time enslaved Black men, women, and children worked as domestics in the homes of White politicians, church clergy, business owners, and other Europeans settlers. Enslaved Blacks cleared land and farmed it for their owners. They constructed buildings and made various products such as potash, soaps, candles, maple syrup, wagons, shoes, and worked in various skilled trades. Following the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1834, Canada attracted thousands of African American freedom-seekers and free Blacks, who settled across Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime provinces. Black workers in the 19th century worked in hired positions and operated a variety of businesses to sustain their families and to develop their local communities. Black wage labourers faced racial discrimination in their work places, the labour market, and in society that century persists to today. They were relegated to the lowest paying jobs, largely in the service industry. Black workers were denied skilled employment and had little recourse as they were initially excluded from the emerging labour movement in the country. To effect change, African Canadians galvanized and challenged the inequality and racism they faced. They held public meetings, wrote petitions, and launched court challenges, all with the aim of tackling racial discrimination, including in employment. In the early 1940s, Black sleeping car porters in Canada began organizing and formed Canadian branches of the all-Black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The book, “My Name’s Not George: the Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada” captures Stanley Grizzle’s experience as a sleeping car porter and WWII veteran. A teacher’s guide is available at www.yorku.ca/acc/library/html, developed by the African Canadian Literature Project. Black workers and their families, a large number of them railway porters, established communities in various parts of the country. In 2014, Canada Post commemorated Hogan’s Valley and Africville with stamps for Black History Month. African Canadians joined efforts with other social groups to lobby the government to address discrimination. Their persistence and activism resulted in the passage of Ontario’s Fair Employment Practices Act in 1951 that set the foundation for improved working conditions and worker’s rights for all Ontarians and Canadians. So why reflect on the experiences and contributions of African Canadian workers from the early 1600s to today? People can gain a deeper appreciation of the long history of Blacks in Canada, to recognize the discrimination they faced, to highlight their determination and vigilance for better working and social conditions, and to show how their efforts have helped to strengthen the Canadian fabric. Critical reflection can also reveal how African Canadian workers broke and continue to break barriers and have made tremendous contributions despite the racial discrimination they encountered. For example, Albert Jackson who, in 1858, was brought as a baby by his mother to freedom in Toronto, was hired as Toronto’s first Black postman in 1882. Rosemary Brown was the first Black woman elected to a provincial legislative in British Columbia in 1972. In 1986 Corrine Sparks became the first provincial judge in Nova Scotia. More recently, in 2012 Devon Clunis of the Winnipeg Police Service became the first Black Police Chief in Canada. One of the most impactful things that Social Studies and History teachers can do in their classrooms is to include visual representations of Black workers, past and present. It is important not only that students of African descent see themselves reflected in the curriculum but that other students see Blacks reflected as equal participants in Canadian society. When I debriefed a Black History Month presentation I conducted with some grade 4 and 5 classes, I asked them what they learned from an activity where they matched the definitions of colonist occupations to the images of Black colonist workers. A student concluded that they learned that African Canadians did jobs that other Canadians did. A simple, but perfect analysis. Labour Day also serves as a call to those who support equity and social justice to continue to fight for racialized workers who face high unemployment, less pay for same work, and seemingly unbreakable glass ceilings. Consider in 2013 that the Ontario unemployment rate for youth between the ages of 15 and 24 was between 16 and 17.1%, higher than the average Canadian range of 13.5 to 14.5%. Statistics show that the unemployment rate for Black youth is the highest amongst any of the visible minority groups at, almost twice the rate of all youth workers. Teachers have to be aware of what their students of African descent face in the working world and work to educate them for success. Racialized students already face barriers to securing employment that reflects their education, skills and abilities. If they don't graduate from high school or don't go on to post-secondary education, we are further crippling their ability to secure employment and be productive citizens. Therefore efforts to engage students in their learning through culturally relevant teaching, for example, and keeping them in school must be a priority. This is one way of ensuring equity in education for African Canadian students, goals set out by the Ministry of Education in Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario for all students in Ontario. All working people are important contributors to our society. The presentation of the working people of in classrooms should be more inclusive of the presence of African Canadians. Teaching students about Canada’s labour movement should include the struggles and experiences of Blacks workers, celebrate the victories against racial discrimination in employment, and encourage young people to take action against the challenges that many workers still face. Suggested Resources: “...and Still I Rise: A History of African Canadian Workers in Ontario, 1900 – Present” (parts of the original exhibit) http://www.museevirtuel-virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitCollection.do?method=previewAbout&lang=EN&id=18598 “...and Still I Rise: A History of African Canadian Workers in Ontario, 1900 – Present” Teacher Guide http://teachingafricancanadianhistory.weebly.com/lesson-plans.html Do you remember the days of slavery? My brother feels it, including my sisters too. Some of us survive, showing them that we are still alive. Do you remember the days of slavery?

- Lyrics from Do You Remember the Days of Slavery?, Burning Spear August 23rd is the International Day for the Remembrance of Slavery and its Abolition. August 23rd was chosen to mark the International Day for the Remembrance of Slavery and its Abolition because on that day in 1791, the Haitian Revolution was initiated by Africans seeking an end to their enslavement. The day is meant to commemorate remember to the approximately 10 million men, women and children who were kidnapped and sent to the New World to be enslaved. It is also a time to remember the countless Africans who perished during the Maafa, the horrendous 400-year slave trade of African bodies, and to remember how enslaved Africans resisted their forced conditions and fought for their freedom. People of African descent were dispersed throughout the colonies of the European empires, forced to labour without pay for the purpose of increasing personal profits and building the wealth of European empires. Canada, as a French and then British colony, was very much part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. European colonists bought and sold African peoples in this country. Canada is also connected to the Transatlantic Slave Trade through the trade of timber, salted cod, and other items with slaveholding Caribbean colonies for slave-produced goods such as rum, molasses, tobacco, and sugar. In classrooms, it’s not about marking the day (which is during the summer break) with students. The International Day for the Remembrance of Slavery and its Abolition is a needed reminder of the related topics needed to be taught throughout the school year and the many opportunities to do so. For the first time, slavery has been included in the newest Ontario Social Studies, History, and Geography curriculum (#ontsshg) as an optional topic in grades 3, 4, 6, and 7. In these grades teachers can teach about the enslavement of Africans and First Nations peoples by French and British colonists in Canada. Law, History, and Social Science teachers in high schools can teach about the laws that supported as well as dismantled the institution of slavery in Canada and internationally. In teaching about slavery, teachers should be careful not to misrepresent to students that Black history begins with enslavement. Mutabaruka, a Jamaican dub poet artist eloquently stated that enslavement “interrupted African history.” The removal of productive people from African societies stagnated their development and changed the trajectory of African history. This means that Africa’s rich and complex history before the Transatlantic Slave Trade should also be taught. In grade 4 under the strand “Early Societies, 3000 BCE – 1500 BCE” there are several African kingdoms that can be incorporated such as the kingdoms of Kush, Nubia, Aksum, Great Zimbabwe, Ghana, Mali, and Egypt. Additionally, Ancient Egypt should be correctly presented as an African civilization. The African Diaspora is a result of the forced global dispersal of Black peoples as a consequence of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and connections to Blacks in places such as Canada, South America, England, the United States, the Caribbean and the continent of Africa can be made in classrooms. Folklore from Africans around the world can be read in language classes. Cultural celebrations of Blacks, such as Emancipation Day, can be highlighted in Grade 2 and other grades. When teaching “Canada’s Interactions with the Global Community” in grade 6, the trade relationships between Canada and African and Caribbean nations can be explored. The various migration streams of Africans into Canada can be included in many grades. The courageous stories of Africans who resisted their enslavement in Canada can also be explored. Henry Lewis, enslaved by William Jarvis, Toronto’s first sheriff and namesake of Jarvis Street and Jarvis Collegiate ran away to New York in 1798 to emancipate himself. In 1793 Chloe Cooley screamed to protest her sale across the Niagara River. Fourteen years after an unsuccessful attempt to free herself and her son, Nancy sought her freedom in the courts of New Brunswick in 1800. Peggy and her children, enslaved in early Toronto by provincial administrator Peter Russell, employed various resistance tactics to the chagrin of their owner. Betty took her baby son and fled the Belleville area in 1818 after exchanging hands several times. Black men fought on behalf of the British in the War of 1812 to secure their freedom and that of their fellow bondsmen and bondswomen. Thousands of enslaved African Americans took the perilous journey to find liberty in Canada. Using these stories, connections can be made to the ways in which Blacks have fought for freedom and for their human rights in our country and places in the world for 200 years. The related issues of colonialism and racism must also be addressed in classrooms because the manifestation of anti-Black racism is fostered by the legacy of slavery. We can’t hope to work towards true social justice and equity if we don’t teach about the systems, attitudes, and practices that operate at the root of inequality and exclusion and persists today in our society. Teachers can share narratives that capture the resilience, genius, bravery, tenacity, fortitude, and contributions of African Canadians and people of African descent around the world in spite of racial oppression and discrimination. Using Diasporic narratives can create a fuller picture of Black history in Canada. Consistent incorporation of Black history - throughout the year and not just in February - over many grades can accomplish a balanced presentation of the many experiences of Africans worldwide. In my presentation at the Routes to Freedom Conference held in Ottawa in March 2008 to commemorate the 200-year anniversary of the end of the abolition of the trade of slaves across the Atlantic, I spoke to the importance of teaching about Canadian slavery: This commemoration presents a timely opportunity for the school system to shift from retaining the African Canadian story to the periphery to making long lasting, impactful changes that would centre it in Canadian history. We as educators are encouraged to teach diversity and promote the acceptance of others which must be extended to the African Canadian experience. Check my list of resources that can be used in the classroom in my Resources pages. |

AuthorNatasha Henry Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||||